Weight loss and increased fitness are desirable at any age, but we tend to think these goals are harder to achieve as we get older. Are they really? Most people are probably primarily motivated to “get in shape” because they want to look better, so what happens when appearance no longer seems so important? There are numerous benefits from exercise and weight loss later in life. This article will explore the relationship between aging and fitness, body composition, and metabolism, and the small lifestyle changes one can make that help fitness become a reality.

The Facts

Over 65% of the American public is currently either overweight (body mass index [BMI] of 25-29) or obese (BMI >30).(1) Current projections suggest that this number will rise to almost 90% by 2030. Beginning in early adulthood, fat mass in the typical person continues to increase until about the age of 60 at which time the weight of the average American stabilizes.(2) This is in part due to the death of the heaviest people aged 50 to 70 years, when the extra weight takes its toll. The remaining elderly tend to maintain their weight or not gain as much as younger people. Lean mass, on the other hand, usually peaks at the age of 20. Those who don’t exercise can lose 40% of their muscle mass from age twenty onward.(5)5 The loss of lean mass with aging (called sarcopenia) is largely responsible for the decrease in resting metabolic rate in older people.(2) What does all of this mean? It tells us the average American is losing muscle and gaining fat from the age of 20 until at least 60.

This is not good news for those wanting to maintain or lose weight because as we age we also tend to move less, which is the primary contributor to adult weight gain. Change can be difficult at any age but often seems harder as we get older. Below are common questions that many older individuals have about fitness and losing weight.

Can I lose weight?

Older individuals may have different reasons for pursuing fitness, but they often have the same goals: less body fat, more muscle, greater strength and endurance. Although men and women of any age can lose weight and become more fit, the concern is often how difficult it will be. Many people believe that after a certain age the body slows so much that losing weight is an arduous task. The reality is that nothing precludes elderly people from weight loss; their bodies still respond to a calorie deficit. However, creating a calorie deficit may seem harder simply because it’s not as easy to move more. Conditions like arthritis make taking the dog for an extra walk or parking further away from your destination s little less appealing. We also tend to be more “set in our ways” when it comes to eating habits.

At my age I am not so concerned about my appearance so why lose weight?

Being overweight is associated with a significantly increased risk for many diseases such as heart disease, cancer and diabetes. Overweight and obesity in the aging population has a few added problems--it is associated with increased fat stored in muscle and around the organs (visceral fat) in addition to the usual storage place under the skin.(3,4) As people age, they lose muscle and gain fat in multiple places, which makes older people fatter at the same weight. In addition, visceral fat and intramuscular fat tend to be more active forms that promote certain diseases. The mechanism is that adipose tissue (fat storage tissue) is metabolically active and can release peptides and cytokines that increase inflammatory signals and exacerbate diseases such as diabetes, coronary artery disease, atherosclerosis and rheumatologic disorders.(5) These chemicals are also associated with an increased risk of insulin resistance, and blood clots. The good news from this research is that moderate dieting and exercise can reverse most of the above-mentioned negative effects and reduce disease risk by up to 50%.(4) You don’t have to become an athlete to reap the benefits either. Older people who lose just 5 to 10% of their starting weight through a simple calorie reduction see significant improvements in cholesterol levels, blood pressure, blood sugar, breathing and tolerance of exercise.(3,6) And the other good news is that weight loss itself trumps the method.(7,8,9,10,11) In other words, other than liposuction, it doesn’t matter how you lose the weight or how you choose to diet.

Benefits of weight loss

Weight loss in those aged 50 to 71 years does not just improve your health profile on paper. The risk of death is greatly reduced among those (in study populations) who were overweight or obese.(12) Studies of heavier older people who lost weight or attempted to lose weight showed they reduced their risk of disease and death, which was attributed to reductions in blood pressure, cholesterol and metabolic rate. Below is a list of a few of the health benefits attributed to weight loss:

- A weight loss of around 10% of the initial body weight was associated with a 33% reduction in the ratio of oxidized LDL to total LDL.(13)

- The meta-analysis by MacMahon et al showed an average decrease in systolic and diastolic blood pressure of 0.68 and 0.34mmHg respectively with each kg of weight loss.(14)

- Men with normal blood pressure survived 7.2 years longer without cardiovascular disease compared to men with high blood pressure, and spent 2.1 fewer years of their lives with cardiovascular disease. There were similar differences in the women studied. Total life expectancy for people with normal blood pressure was 5.1 years longer in men and 4.9 years longer in women than in people with high blood pressure.(15)

- Diabetic men and women 50 years and older lived on average 7.5 and 8.2 years less than their nondiabetic equivalents. The differences in life expectancy free of CVD were 7.8 and 8.4 years, respectively.(16)

- Moderate and high physical activity levels led to 1.3 and 3.7 years more in total life expectancy and 1.1 and 3.2 more years lived without cardiovascular disease, respectively, for men aged 50 years or older compared with those who maintained a low physical activity level. For women the differences were 1.5 and 3.5 years in total life expectancy and 1.3 and 3.3 more years lived free of cardiovascular disease, respectively.(17)

- Individuals in the Framingham cohort who lost at least 5LBS over 16 years, had a 40 –50% reduction in their total risk factor score. In contrast, those who gained as little as 5LBS had a 20 –40% increase, depending on gender, in that same score.(13)13

Hasn’t my metabolism slowed so much that weight loss will be almost impossible?

Losing weight at an advanced age should not be any more difficult than for the younger population. In fact, weight loss should be easier for seniors because they generally have more time to increase their daily movements than busy younger family members. And no, one’s

metabolism is not the problem.

Your metabolism, or 24-hour energy expenditure (TEE), is the total of all the processes in the body that require energy. The biggest part of the body’s total energy expenditure is called the resting metabolic rate (RMR), which is the number of calories required to run the body when sitting quietly. The RMR usually makes up two-thirds to three-fourths of the total calories burned daily. The remaining energy expenditure includes the calories required to move throughout the day (which is the part that we all have total control over) and calories burned to digest food (called the thermic effect of food, TEF). Aging can slightly decrease RMR mostly due to the loss of lean muscle over time. But this is generally offset by total weight gain – i.e. the heavier you are the more calories you burn, even if much of your body weight gain is mostly fat. In any case, the more significant decrease in total energy expenditure in the aging population is caused by the reduction in total daily activities/movement. Again, this is something we do have control over. Unfortunately, as we age we get tired easier, lifestyles change, and it often hurts to move. These are all conditions that lead to less movement thus less 24 hour energy expenditure (calories burned). This is what the average person incorrectly attributes to a slowing metabolism.

Exercise can increase RMR by helping one build lean muscle and therefore offsetting the slight muscle loss attributed to aging. At worst, exercise can prevent the decrease that occurs in one’s resting metabolic rate by helping to maintain LBM.(4)4 And of course the act of exercise (or any additional increases in daily activities) dramatically increases the calories you burn daily. So there you have it, you have complete control of your metabolism no matter how old you are – just get up and move. And remember, standing burns almost twice as many calories as sitting and walking nearly 3 times as many.

Why do resistance training?

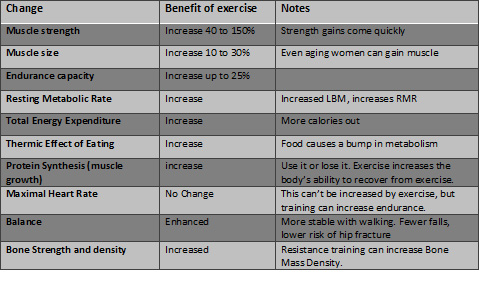

Aging is associated with a decrease in aerobic capacity and muscular strength. Exercise can reverse both conditions. Performing aerobic exercise can increase aerobic capacity in the elderly by almost 25%.(18) Several studies designed to measure strength gains from resistance training in the elderly demonstrated an average increase in strength of 40 to 150% in just three to six months.(4) Muscular growth may be slightly less in older subjects compared to younger, but strength gains are similar in both age groups when first starting out. The harder the older subjects were pushed in these studies, the more their bodies responded with muscle and strength gains. One of the many benefits of such training is that balance is improved in exercisers, which can lead to fewer falls and hip fractures, and decreased death rates from their complications. Exercise also dramatically improves the ability to perform daily functions, allowing a longer life of independence.

Table 1: Changes from aging that are reversed or minimized by exercise.

Partially adapted from “Singh MA. Exercise comes of age: rationale and recommendations for a geriatric exercise prescription. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2002 May;57(5):M262-82.”

If I lose weight at my age will I also lose muscle?

When older people gain weight unintentionally, more body fat is gained than lean mass, which is similar to what happens with younger people.(19) Up to twenty-five percent of intentional weight loss (dieting) in older people is from lean mass and seventy-five percent is from fat, which is also similar to young people. This loss of lean tissue from dieting can be reduced significantly by resistance exercise, bringing the percentage of weight lost as lean mass to between 0 and 12%.(19)

Sarcopenia is age-related loss of lean mass, as described earlier, and is not associated with intentional weight loss or dieting. Resistance training is the antidote for sarcopenia.(20)

Final Note

Keep in mind that beneficial exercise can be as simple as moving. In fact, walking is the most common form of exercise. Dieting can be as simple as reducing the portions of the foods you generally consume. Therefore, for those of you just contemplating a fitness routine, don’t be put off or say you’re not ready because you believe fitness requires a lifestyle change or hard work. Fitness is really a matter of minor lifestyle adjustments. Your food can be your diet and your life is exercise. Start there and watch what happens.

References

- Wang Y, Beydoun MA, Liang L, Caballero B, Kumanyika SK. Will all Americans become overweight or obese? estimating the progression and cost of the US obesity epidemic. Obesity. 2008 Oct;16(10):2323-30. Epub 2008 Jul 24.

- Villareal DT, Apovian CM, Kushner RF, Klein S; American Society for Nutrition; NAASO, The Obesity Society. Obesity in older adults: technical review and position statement of the American Society for Nutrition and NAASO, The Obesity Society. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005 Nov;82(5):923-34.

- Mazzali G, Di Francesco V, Zoico E, Fantin F, Zamboni G, Benati C, Bambara V, Negri M, Bosello O, Zamboni M. Interrelations between fat distribution, muscle lipid content, adipocytokines, and insulin resistance: effect of moderate weight loss in older women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006 Nov;84(5):1193-9.

- Singh MA. Exercise comes of age: rationale and recommendations for a geriatric exercise prescription. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2002 May;57(5):M262-82.

- Jarosz PA, Bellar A. Age-appropriate obesity treatment.Nurse Pract. 2008 May;33(5):24-31.

- Weinkove C. Obesity in Tallis RC, FIllit HM [Editors] Brockhurst’s Textbook of Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology 6th Edition. Elsevier Science Limited: Philadelphia PA; 2003 pp 1073-9.

- Schoeller DA, Buchholz AC. Energetics of obesity and weight control: does diet composition matter? J Am Diet Assoc. 2005 May;105(5 Suppl 1):S24-8. Review.

- Brehm BJ, D'Alessio DA. Weight loss and metabolic benefits with diets of varying fat and carbohydrate content: separating the wheat from the chaff. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2008 Mar;4(3):140-6. Epub 2008 Jan 29. Review.

- McAuley KA, Smith KJ, Taylor RW, McLay RT, Williams SM, Mann JI. Long-term effects of popular dietary approaches on weight loss and features of insulin resistance. Int J Obes (Lond). 2006 Feb;30(2):342-9.

- Liebman, B. "Diabetes. How to Play Defense" Nutrition Action Healthletter Sep. 2008: 4.

- Tinker LF, Bonds DE, Margolis KL, Manson JE, Howard BV, Larson J, Perri MG, Beresford SA, Robinson JG, Rodríguez B, Safford MM, Wenger NK, Stevens VJ, Parker LM; Women's Health Initiative. Low-fat dietary pattern and risk of treated diabetes mellitus in postmenopausal women: the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled dietary modification trial. Arch Intern Med. 2008 Jul 28;168(14):1500-11.

- Adams KF, Schatzkin A, Harris TB, Kipnis V, Mouw T, Ballard-Barbash R, Hollenbeck A, Leitzmann MF. Overweight, obesity, and mortality in a large prospective cohort of persons 50 to 71 years old. N Engl J Med. 2006 Aug 24;355(8):763-78. Epub 2006 Aug 22.

- Vidal J, Updated review on the benefits of weight loss. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2002 Dec;26 Suppl 4:S25-8. Review.

- MacMahon S, Cutler J, Brittain E, Higgins M. Obesity and hypertension: epidemiological and clinical issues. Eur Heart J. 1987 May;8 Suppl B:57-70. Review.

- Franco OH, Peeters A, Bonneux L, de Laet C. Blood pressure in adulthood and life expectancy with cardiovascular disease in men and women: life course analysis. Hypertension. 2005 Aug;46(2):280-6. Epub 2005 Jun 27.

- Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, Lachin JM, Walker EA, Nathan DM; Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002 Feb 7;346(6):393-403.

- Franco OH, de Laet C, Peeters A, Jonker J, Mackenbach J, Nusselder W. Effects of physical activity on life expectancy with cardiovascular disease. Arch Intern Med. 2005 Nov 14;165(20):2355-60.

- Lambert CP, Evans WJ. Adaptations to aerobic and resistance exercise in the elderly. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2005 May;6(2):137-43.

- Newman AB, Lee JS, Visser M, Goodpaster BH, Kritchevsky SB, Tylavsky FA, Nevitt M, Harris TB. Weight change and the conservation of lean mass in old age: the Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005 Oct;82(4):872-8.

- Ferrara CM, McCrone SH, Brendle D, Ryan AS, Goldberg AP. Metabolic effects of the addition of resistive to aerobic exercise in older men. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2004 Feb;14(1):73-80.

-